Yesterday, in part one of this two-part series on a Stöckl’ interview featuring Conchita Wurst and Hape Kerkeling, I talked about Conchita meeting another one of her idols (Kerkeling), her incredible focus, and the intense fame she has found herself surrounded by since Eurovision 2014.

Today, I’m starting off with a look at how Conchita chooses the projects she decides to do, but only because I’m intrigued by the way in which she explains it here.

As when interviewer Barbara Stöckl asks about the 2,000 requests for her time supposedly waiting in her office — “How do you decide what you’re going to pick up and what not?” — she flips the reply on its head when it comes to what you might expect.

Because she specifically talks about reality TV shows; after her involvement in a German reality TV show called ‘Wild Girls‘, and in another in which she worked in a fish factory.

But instead of saying, like other celebrities might, that reality TV shows are cheesy, that they are edited deliberately to show most participants in a poor light and, quite frankly, would be a bad career move for her at this point in her life, she instead takes the blame on herself to explain why she will never do another one.

“I did some reality TV but I am absolutely not cut out for that…I’m much too boring……This genre I’ve eliminated completely where these interview requests are concerned, because I can’t offer anything. I couldn’t do it naturally without distorting myself.”

And I admit, when I first became interested in Conchita and she gave answers in this diplomatic way she has, I found her annoying. Because I’m used to American and British celebrities who are often more direct and so, to some extent, seemed more real.

But the more I’ve watched her the more I now agree with her diplomatic approach. As it’s just this respectfulness, and kindness, and refusal to hurt anyone’s feelings, even those of a reality TV show director, that is not only what everyone talks about after they have met her, but is also helping to change people’s minds about her.

Because, I’d say, it’s difficult for most people to continue hating a bearded, long-haired, long-lashed, couture-dressed, high-heeled, drag artist, when she’s just so absolutely lovely. Even when you’re not.

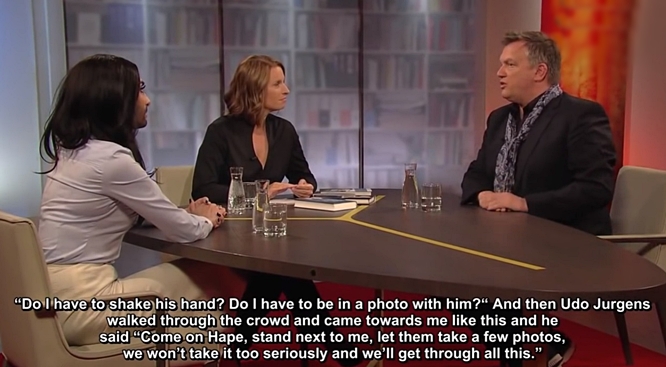

Further on in the interview too, there’s a lovely moment with Hape Kerkeling where he talks about being deliberately outed in 1991 by filmmaker Rosa von Praunheim.

The same day, Kerkeling was at the Bambi Awards where he was avoided by many of his colleagues now they knew he was gay, as they didn’t want to have their photographs taken with him. (And you can only imagine how hurtful that must have been for Kerkeling. Standing on a red carpet knowing people, some of whom he probably classified as friends, were not wanting to be associated with him anymore because of his sexual orientation).

But Austrian singer Udo Jürgens, who must have seen Kerkeling being shunned, walked right up to him and said, “Come on, Hape. Stand next to me. Let them take a few photos. We won’t take it too seriously, and we’ll get through all this”.

And you can tell how much love and respect Kerkeling had for Jürgens after that. As here was someone who wasn’t going to stand by and do nothing, while bigots, homophobes and cowards hurt a man who didn’t deserve it.

On the subject of bigotry, later on Conchita is asked about those who, instead of congratulating Conchita Wurst after her Eurovision win, congratulated her alter ego Tom Neuwirth. And, as Barbara Stöckl says, “I think you understood their clear message? How did you perceive that?”

And Conchita admits, of course, she understood their message (the refusal to admit Conchita Wurst exists, so referencing Tom instead, belittles who she is and what she does, and is a sure sign of bigotry).

But what is interesting here is not so much what Conchita says in answer to the question. It’s what Hape Kerkeling does in response to what she says, as his response says an awful lot about her.

Because Conchita kindly gives the somewhat bigots the benefit of the doubt, and makes the decision to think they were being nice and not derogatory.

“Of course I understood their message. First of all, I was happy about it, and secondly I thought about how much overcoming it must have taken to phrase this nice statement”.

And when she says, “how much overcoming it must have taken to phrase this nice statement”, Kerkeling sniggers. Because he, like me, knows exactly what those messages meant and, in most cases, they certainly weren’t meant to be ‘nice’.

But then watch his face.

Because, it’s obvious to me, Conchita not only didn’t join him in his snigger, she refused to acknowledge it at all, as Kerkeling almost immediately stops smiling and looks a little ashamed.

And, having met Conchita Wurst, I can say it’s something she does. Because she did it with me.

It’s a thing where, if she does not agree with you or has decided she’s not going to react to something you said, she has such a singularity of mind, a stubbornness if you will, she just looks right at you as if that thing you just said never got said at all.

To someone like Kerkeling, that was enough to make him rethink his reaction. To someone like me, who is equally as stubborn as her, it was just something to file away in my head under things titled “Interesting Conchita Wurst responses”.

And while there are five thousand other things I could still talk about from this ‘Stöckl‘ interview, I’m going to close with a thought on Conchita’s response to a question about the ‘old Conchita’. The one who was loud, and over the top, and a little annoying. The one who wasn’t going to Eurovision, and didn’t get to wear couture clothes.

Because Stöckl asks about the Conchita backstory. You know the one. Where Conchita is from the Colombian highlands, with a father who was a German theater manager, and more than a dozen sisters. The story we don’t hear anymore.

And Stöckl asks her, “I have a feeling it was lost, or maybe has crumbled a little, this biography. It seems as if Conchita has been ashamed of her background ever since she got famous”.

Conchita, herself, starts to answer and then stops and does this fabulous snort, as if to say she knows exactly how silly that backstory was. She created it. And now she can laugh at it. And laugh at herself.

And this is what is so wonderful about Conchita Wurst. Because while, yes, there’s definitely a touch of stubbornness, it is also overshadowed by a person who is so sure of who she now is, and so comfortable with that, she is perfectly able to laugh at herself when the need arises.

But I also have to say I do think Barbara Stöckl got it wrong when she suggested Conchita was “ashamed” of who she used to be. As I don’t think it is that at all.

I think it’s that, as Conchita herself explains, when Conchita Wurst first appeared she tried to fit into the gay community’s idea of who and what a drag artist should be. That means being someone who is loud, tacky and, yes, annoying. Because that’s what it usually takes to be taken ‘seriously’ as a drag artist.

Since Eurovision, though, Conchita has suddenly found herself being taken seriously for two very different reasons. As someone who is both a serious artist with a powerhouse voice, and a human rights icon.

And that is the real beauty behind Conchita Wurst’s Eurovision win, and what it has meant to her. It has allowed her to be taken seriously for who she really is.

Not a stereotypical drag queen getting cheap laughs by being obnoxiously over the top. Because that was never her. And if you watch the videos of her behaving that way, you can see it wasn’t, as she looks so uncomfortable doing it.

But instead someone who is kind, respectful, far more shy than you would expect, and quite a lot more serious. With a personality that is very mature, especially for someone still so young, and who has such a built in elegance about her it’s no wonder the old Conchita found behaving the way she did so exhausting.

So, no, Conchita Wurst isn’t ashamed of her old story or her old self at all. She’s just finally now allowed to be who she always was. And isn’t that the most lovely thing of all.